In 1854, the photographer Alphonse-Eugene Disdéri patented a process that could be used to take several portraits in a row on one plate. The small-format Cartes-de-Visite, served the social exchange, comparable to today’s business cards. They were perceived in French society in the late 19th century as a representation of a person.

Disdéri also planned to develop a process by which he could print the portraits on garments.

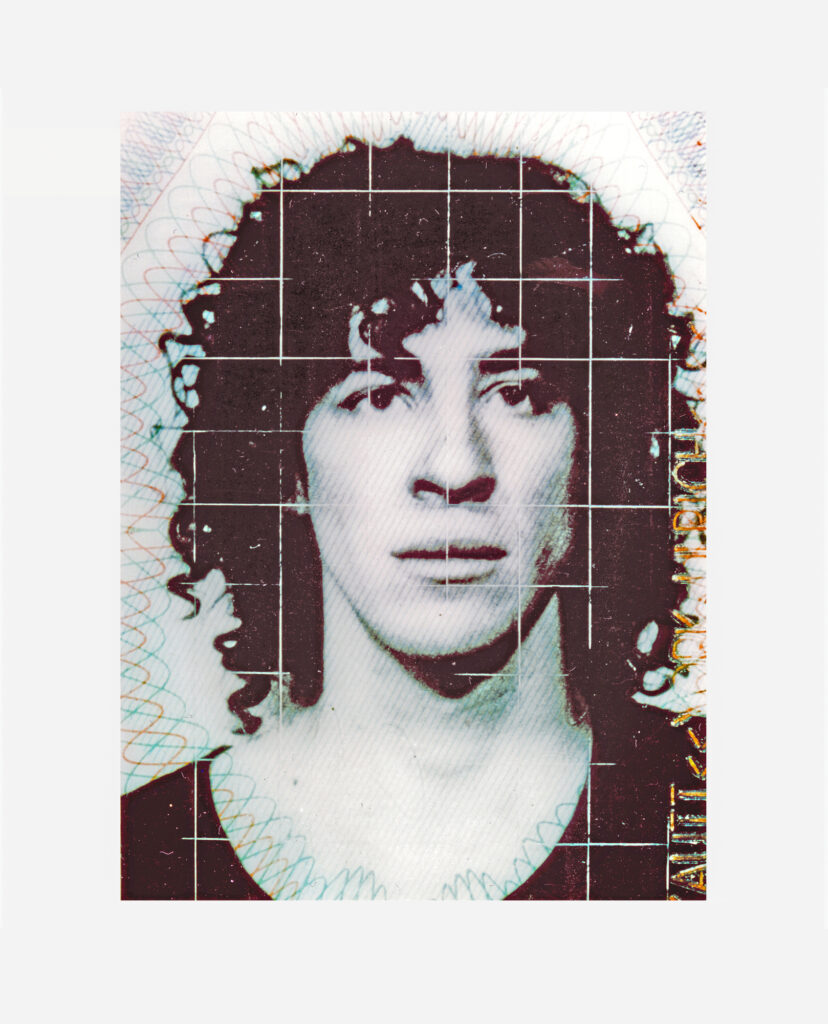

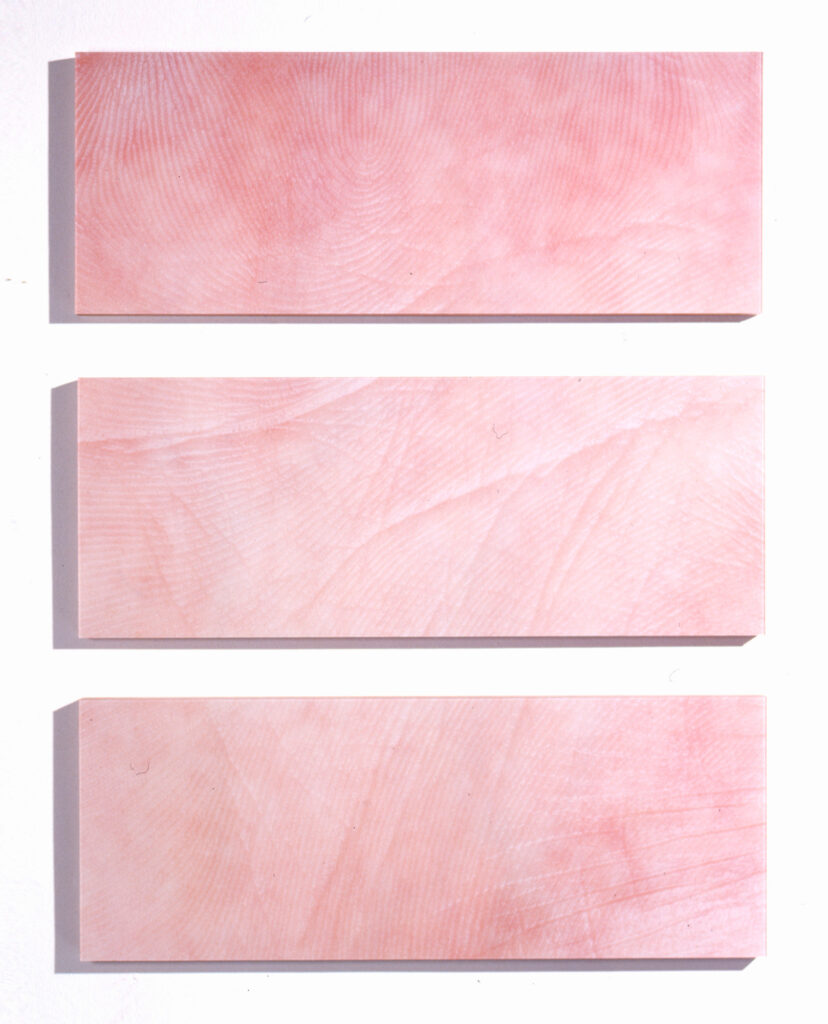

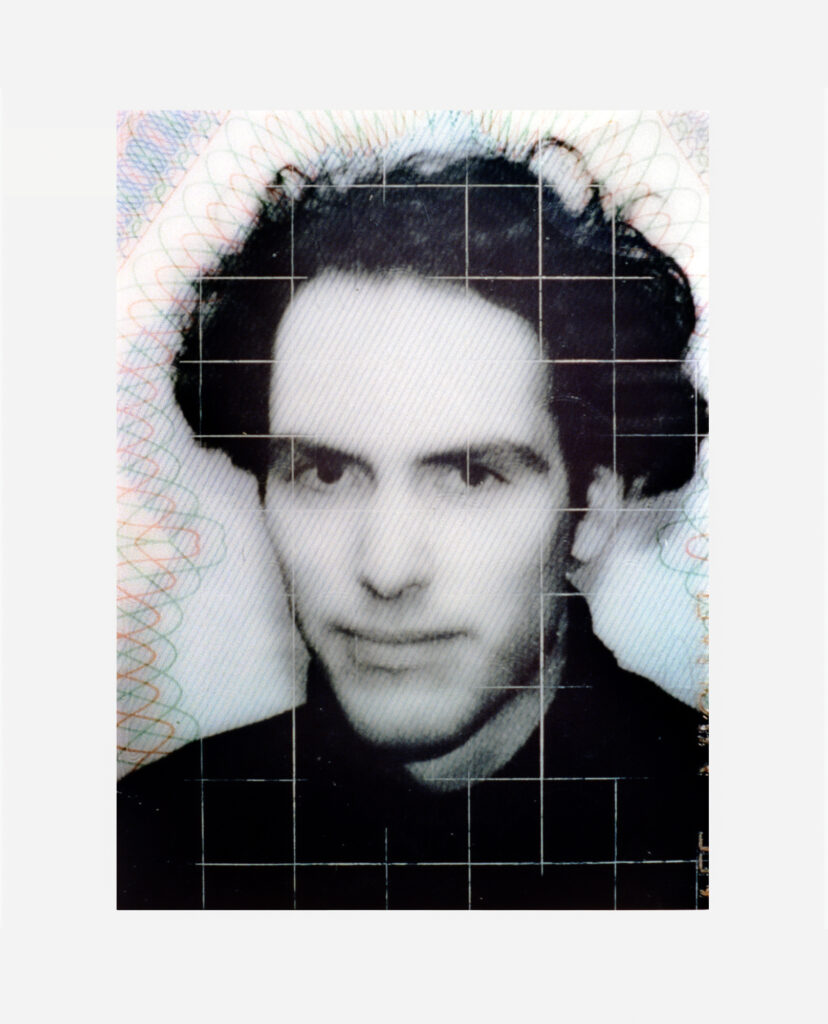

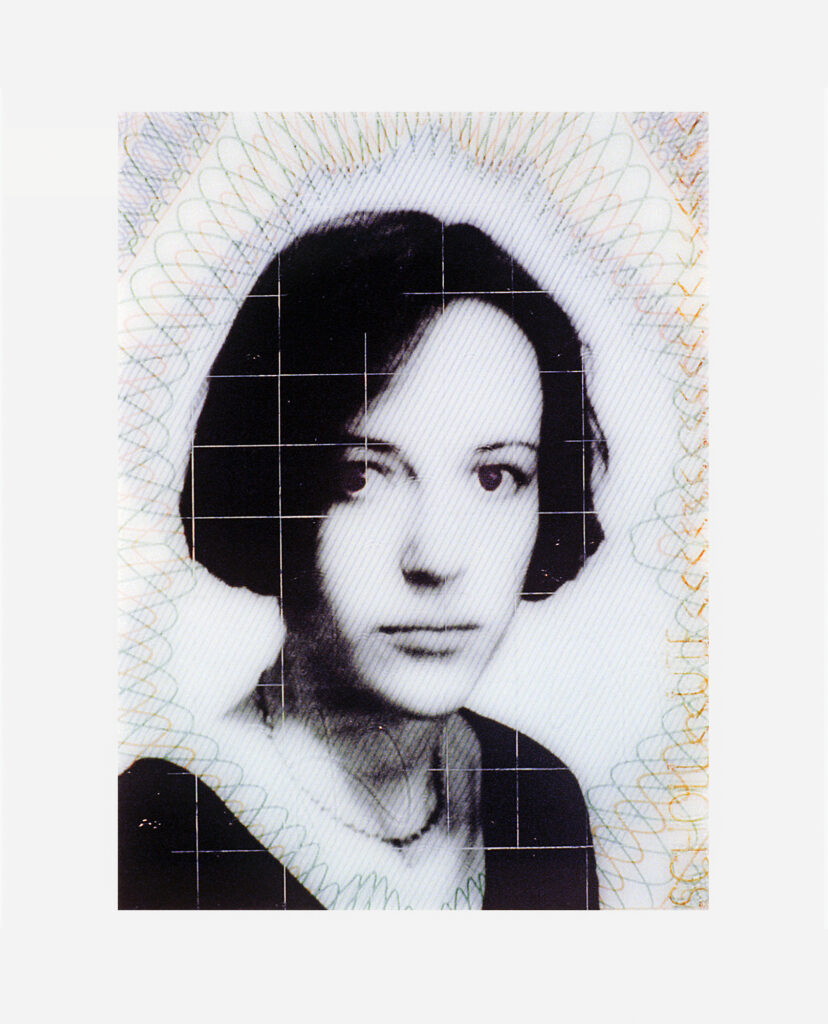

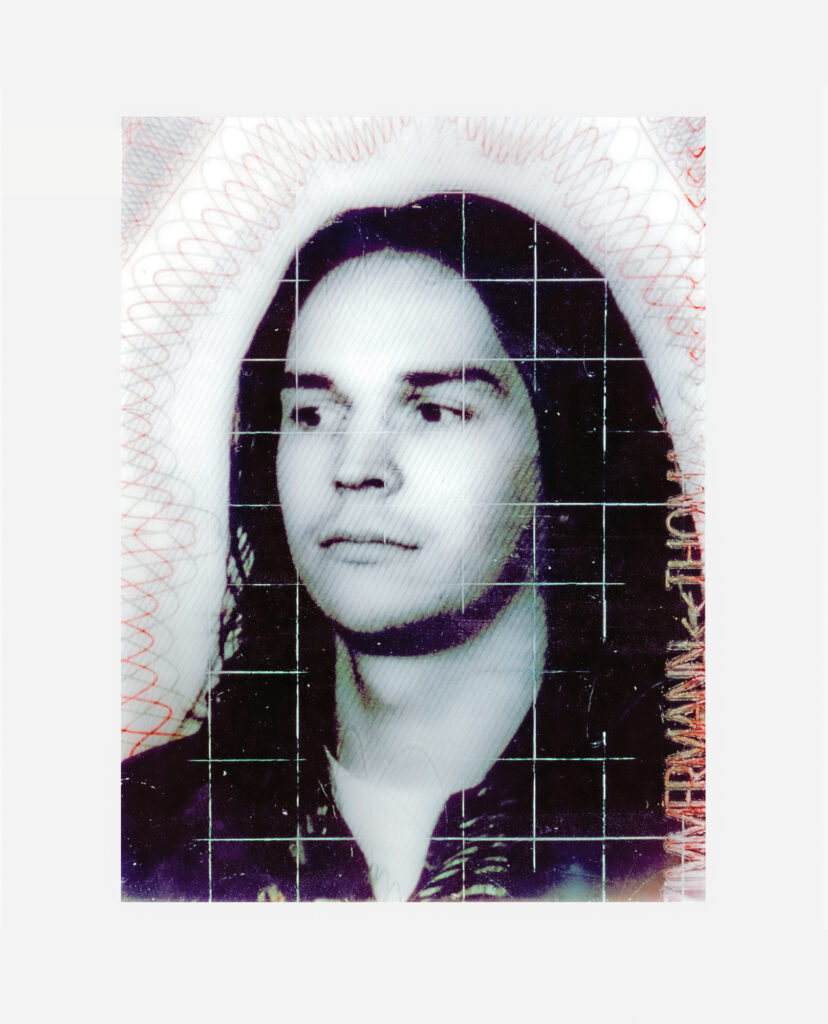

Since April 1, 1987, there has been the machine-readable, forgery-proof identity card, which is produced centrally in the privatized Berlin Bundesdruckerei and for which a “possession obligation” was issued by law. The “portraits” are large-format reproductions of identity card images (1990-1993) as well as a photographic hand-line image. Through the selection of motifs, the presentation as pictorial objects and the installation in the series, the “Portraits” not only establish an analogy to the Cartes-de-Visite but also a reference to the beginnings of portrait painting in the Renaissance.

Traces and testimonies of the pictorial representation of the individual can be found in individual handprints next to the cave paintings of the Stone Age as well as in ancient Roman wall paintings in Pompej and then again in the Renaissance, the actual birth of the image of man we are familiar with today.

Hans Belting wrote in his 2008 book “Florence and Baghdad”: The Renaissance portrayed the human subject, which it celebrated as an individual, in two ways. She did it on the one hand through his portrait and on the other hand through his gaze, which was reflected in the picture. Portrait and perspective image were invented independently of each other, but at the same time. Both give the human being a symbolic presence in the picture, because he appears in the portrait with his face and in the perspective picture with his view of the world. Perspective and portrait art are both a symbolic form.”

- Portrait I Portrait I C-Print, 156 x 123 cm 1993

- Handlinien Handlinien3 C-Prints each 48 x 123 cm1993

- Portrait II Portrait II C-Print, 156 x 123 cm 1993

- Portrait III Portrait III C-Print, 156 x 123 cm 1993 Denn die Evolution, das Handeln, ein geschichtlicher Ablauf, eine Bewegung, eine Erzeugung von Sinn können nicht ohne Unterscheidungen auskommen, es sind dies jedoch Millionen von Unterscheidungen. Bei der Ideologie besteht das Problem darin, dass sie, sobald sie sich als Ideologie formiert und sichtbar wird, bereits eine Ruine ist, da nur eine Unterscheidung getroffen wurde, in welcher sie verharrt und die einen Stillstand beschwört, den Verfall von vornherein impliziert und das Reale bereits mit dem Tod eingetauscht hat. Die Ideologie feiert ihren eigenen Tod, indem sie, „wie die Camera Obscura, die Realität auf den Kopf stellt“ und versucht, den Stillstand bis ins Unendliche hinauszuzögern. -Im Blick der Bilder-, 2023

- Portrait V Portrait V C-Print, 156 x 123 cm 1993